| “We don’t do [ Iraqi ] body counts.” |

IRAQ WAR CO$T

(JavaScript Error)

u.s. dead the coffins iraqi casualties |

|

|

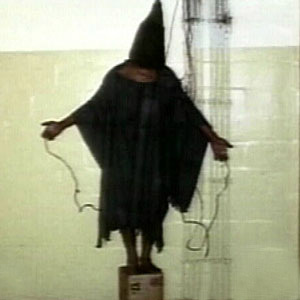

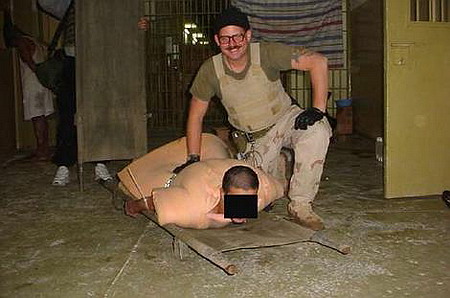

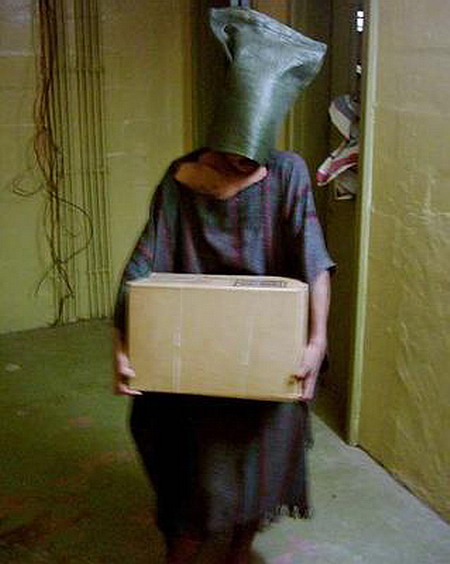

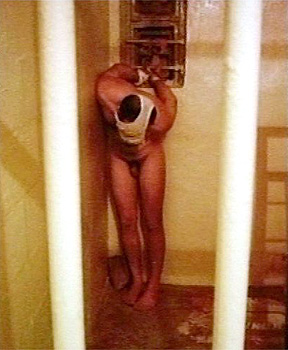

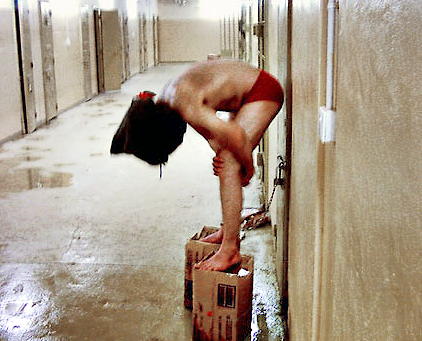

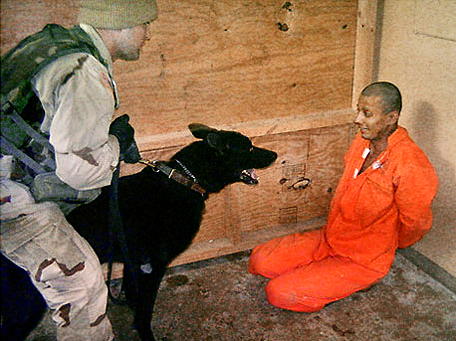

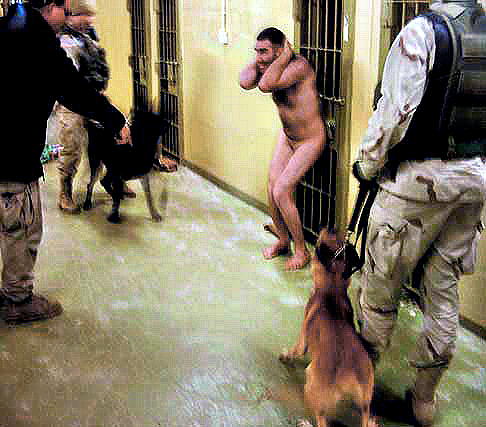

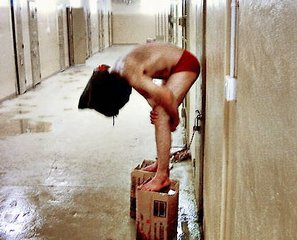

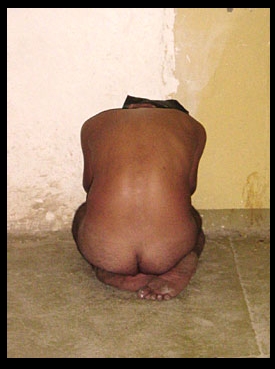

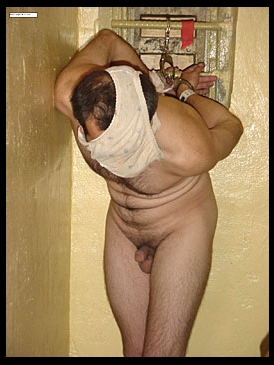

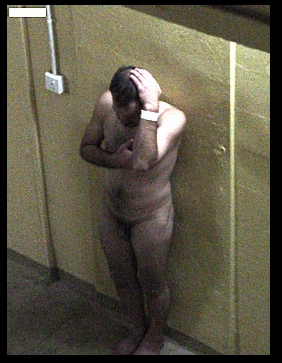

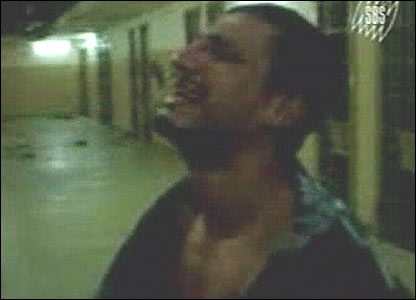

guantánamo & abu graib 2 |

|

|

|

"If we believe absurdities, we shall commit atrocities."

"When you fight evil it can embrace you."

"We had the moral right, we had the duty, to destroy the people

who wanted to destroy us. We have fulfilled this most difficult duty

for the love of our people. And our spirit, our soul, our character has not

suffered injury from it."

"It is our duty as Americans to use the military to go into the world and make the

world like us."

"The best political weapon is the weapon of terror. Cruelty commands respect. Men

may hate us. But, we don't ask for their love; only for their fear."

"I do not see why man should not be just as cruel as nature."

"There's no -- no one in this government, here or on the ground, is going to underreport what's happening.

That's just terrible to think that. Even to suggest it is outrageous. Most certainly not!"

"This war has been advanced on lie upon lie. Iraq was not responsible for 9/11. Iraq was not responsible for any

role al-Qaeda may have had in 9/11. Iraq was not responsible for the anthrax attacks on this country. Iraq did not

tried to acquire nuclear weapons technology from Niger. This war is built on falsehood."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

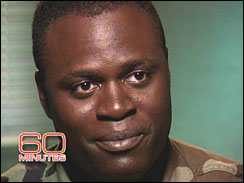

The General's Report

How Antonio Taguba, who investigated the Abu Ghraib scandal, became one of its casualties

If there was a redeeming aspect to the affair, it was in the thoroughness and the passion of the Army's initial investigation. The inquiry had begun in January, and was led by General Taguba, who was stationed in Kuwait at the time. Taguba filed his report in March. In it he found:

Taguba was met at the door of the conference room by an old friend, Lieutenant General Bantz J. Craddock, who was Rumsfeld's senior military assistant. Craddock's daughter had been a babysitter for Taguba's two children when the officers served together years earlier at Fort Stewart, Georgia. But that afternoon, Taguba recalled, "Craddock just said, very coldly, 'Wait here.' " In a series of interviews early this year, the first he has given, Taguba told me that he understood when he began the inquiry that it could damage his career; early on, a senior general in Iraq had pointed out to him that the abused detainees were "only Iraqis." Even so, he was not prepared for the greeting he received when he was finally ushered in.

"Here ... comes ... that famous General Taguba - of the Taguba report!" Rumsfeld declared, in a mocking voice. The meeting was attended by Paul Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld's deputy; Stephen Cambone, the Under-Secretary of Defense for Intelligence; General Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (J.C.S.); and General Peter Schoomaker, the Army chief of staff, along with Craddock and other officials. Taguba, describing the moment nearly three years later, said, sadly, "I thought they wanted to know. I assumed they wanted to know. I was ignorant of the setting."

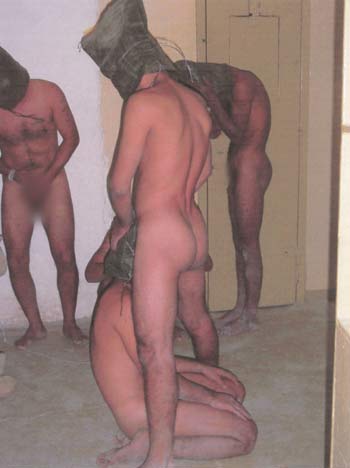

In the meeting, the officials professed ignorance about Abu Ghraib. "Could you tell us what happened?" Wolfowitz asked. Someone else asked, "Is it abuse or torture?" At that point, Taguba recalled, "I described a naked detainee lying on the wet floor, handcuffed, with an interrogator shoving things up his rectum, and said, 'That's not abuse. That's torture.' There was quiet."

Rumsfeld was particularly concerned about how the classified report had become public. "General," he asked, "who do you think leaked the report?" Taguba responded that perhaps a senior military leader who knew about the investigation had done so. "It was just my speculation," he recalled. "Rumsfeld didn't say anything." (I did not meet Taguba until mid-2006 and obtained his report elsewhere.) Rumsfeld also complained about not being given the information he needed. "Here I am," Taguba recalled Rumsfeld saying, "just a Secretary of Defense, and we have not seen a copy of your report. I have not seen the photographs, and I have to testify to Congress tomorrow and talk about this." As Rumsfeld spoke, Taguba said, "He's looking at me. It was a statement."

At best, Taguba said, "Rumsfeld was in denial." Taguba had submitted more than a dozen copies of his report through several channels at the Pentagon and to the Central Command headquarters, in Tampa, Florida, which ran the war in Iraq. By the time he walked into Rumsfeld's conference room, he had spent weeks briefing senior military leaders on the report, but he received no indication that any of them, with the exception of General Schoomaker, had actually read it. (Schoomaker later sent Taguba a note praising his honesty and leadership.) When Taguba urged one lieutenant general to look at the photographs, he rebuffed him, saying, "I don't want to get involved by looking, because what do you do with that information, once you know what they show?"

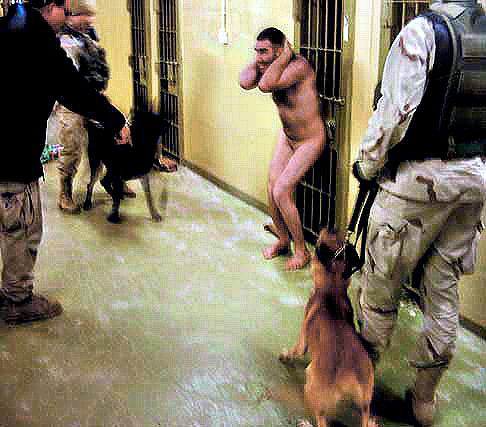

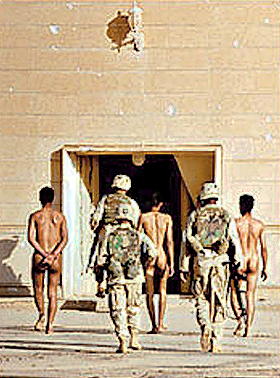

Taguba also knew that senior officials in Rumsfeld's office and elsewhere in the Pentagon had been given a graphic account of the pictures from Abu Ghraib, and told of their potential strategic significance, within days of the first complaint. On January 13, 2004, a military policeman named Joseph Darby gave the Army's Criminal Investigation Division (C.I.D.) a CD full of images of abuse. Two days later, General Craddock and Vice-Admiral Timothy Keating, the director of the Joint Staff of the J.C.S., were e-mailed a summary of the abuses depicted on the CD. It said that approximately ten soldiers were shown, involved in acts that included:

Taguba said, "You didn't need to 'see' anything - just take the secure e-mail traffic at face value."

I learned from Taguba that the first wave of materials included descriptions of the sexual humiliation of a father with his son, who were both detainees. Several of these images, including one of an Iraqi woman detainee baring her breasts, have since surfaced; others have not. (Taguba's report noted that photographs and videos were being held by the C.I.D. because of ongoing criminal investigations and their "extremely sensitive nature.") Taguba said that he saw "a video of a male American soldier in uniform sodomizing a female detainee." The video was not made public in any of the subsequent court proceedings, nor has there been any public government mention of it. Such images would have added an even more inflammatory element to the outcry over Abu Ghraib. "It's bad enough that there were photographs of Arab men wearing women's panties," Taguba said.

On January 20th, the chief of staff at Central Command sent another e-mail to Admiral Keating, copied to General Craddock and Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, the Army commander in Iraq. The chief of staff wrote, "Sir: update on alleged detainee abuse per our discussion. DID IT REALLY HAPPEN? Yes, currently have 4 confessions implicating perhaps 10 soldiers. DO PHOTOS EXIST? Yes. A CD with approx 100 photos and a video - CID has these in their possession."

In subsequent testimony, General Myers, the J.C.S. chairman, acknowledged, without mentioning the e-mails, that in January information about the photographs had been given "to me and the Secretary up through the chain of command... . And the general nature of the photos, about nudity, some mock sexual acts and other abuse, was described."

Nevertheless, Rumsfeld, in his appearances before the Senate and the House Armed Services Committees on May 7th, claimed to have had no idea of the extensive abuse. "It breaks our hearts that in fact someone didn't say, 'Wait, look, this is terrible. We need to do something,' " Rumsfeld told the congressmen. "I wish we had known more, sooner, and been able to tell you more sooner, but we didn't."

Rumsfeld told the legislators that, when stories about the Taguba report appeared, "it was not yet in the Pentagon, to my knowledge." As for the photographs, Rumsfeld told the senators, "I say no one in the Pentagon had seen them"; at the House hearing, he said, "I didn't see them until last night at 7:30." Asked specifically when he had been made aware of the photographs, Rumsfeld said:

"And, as a result, somebody just sent a secret report to the press, and there they are," Rumsfeld said.

Taguba, watching the hearings, was appalled. He believed that Rumsfeld's testimony was simply not true. "The photographs were available to him - if he wanted to see them," Taguba said. Rumsfeld's lack of knowledge was hard to credit. Taguba later wondered if perhaps Cambone had the photographs and kept them from Rumsfeld because he was reluctant to give his notoriously difficult boss bad news. But Taguba also recalled thinking, "Rumsfeld is very perceptive and has a mind like a steel trap. There's no way he's suffering from C.R.S. - Can't Remember Shit. He's trying to acquit himself, and a lot of people are lying to protect themselves." It distressed Taguba that Rumsfeld was accompanied in his Senate and House appearances by senior military officers who concurred with his denials.

"The whole idea that Rumsfeld projects - 'We're here to protect the nation from terrorism' - is an oxymoron," Taguba said. "He and his aides have abused their offices and have no idea of the values and high standards that are expected of them. And they've dragged a lot of officers with them."

In response to detailed queries about this article, Colonel Gary Keck, a Pentagon spokesman, said in an e-mail, "The department did not promulgate interrogation policies or guidelines that directed, sanctioned, or encouraged abuse." He added, "When there have been abuses, those violations are taken seriously, acted upon promptly, investigated thoroughly, and the wrongdoers are held accountable." Regarding early warnings about Abu Ghraib, Colonel Keck said, "Former Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld has stated publicly under oath that he and other senior leaders were not provided pictures from Abu Ghraib until shortly before their release." (Rumsfeld, through an aide, declined to answer questions, as did General Craddock. Other senior commanders did not respond to requests for comment.)

During the next two years, Taguba assiduously avoided the press, telling his relatives not to talk about his work. Friends and family had been inundated with telephone calls and visitors, and, Taguba said, "I didn't want them to be involved." Taguba retired in January, 2007, after thirty-four years of active service, and finally agreed to talk to me about his investigation of Abu Ghraib and what he believed were the serious misrepresentations by officials that followed. "From what I knew, troops just don't take it upon themselves to initiate what they did without any form of knowledge of the higher-ups," Taguba told me. His orders were clear, however: he was to investigate only the military police at Abu Ghraib, and not those above them in the chain of command. "These M.P. troops were not that creative," he said. "Somebody was giving them guidance, but I was legally prevented from further investigation into higher authority. I was limited to a box."

General Taguba is a slight man with a friendly demeanor and an unfailingly polite correctness. "I came from a poor family and had to work hard," he said. "It was always shine the shoes on Saturday morning for church, and wash the car on Saturday for church. And Saturday also for mowing the lawn and doing yard jobs for church."

His father, Tomas, was born in the Philippines and was drafted into the Philippine Scouts in early 1942, at the height of the Japanese attack on the joint American-Filipino force led by General Douglas MacArthur. Tomas was captured by the Japanese on the Bataan peninsula in April, 1942, and endured the Bataan Death March, which took thousands of American and Filipino lives. Tomas escaped and joined the underground resistance to the Japanese before returning to the American Army, in July, 1945.

Taguba's mother, Maria, spent much of the Second World War living across the street from a Japanese-run prisoner-of-war camp in Manila. Taguba remembers her vivid accounts of prisoners who were bayonetted arbitrarily or whose fingernails were pulled out. Antonio, the eldest son (he has six siblings), was born in Manila in 1950. Maria and Tomas were devout Catholics, and their children were taught respect and, Taguba recalls, "above all, integrity in how you lived your life and practiced your religion."

In 1961, the family moved to Hawaii, where Tomas retired from the military and took a civilian job in logistics, preparing units for deployment to Vietnam. A year after they arrived, Antonio became a U.S. citizen. By then, as a sixth grader, he was delivering newspapers, serving as an altar boy, and doing well in school. He went to Idaho State University, in Pocatello, with help from the Army R.O.T.C., and graduated in 1972. As a newly commissioned second lieutenant, he was five feet six inches tall and weighed a hundred and twenty pounds. His Army service began immediately: he led troops at the platoon, company, battalion, and brigade levels at bases in South Korea, Germany, and across America. (He married in 1981, and has two grown children.) In 1986, Taguba, then a major, was selected to attend the College of Naval Command and Staff at the Naval War College, in Newport, Rhode Island. While there, he wrote an analysis of Soviet ground-attack planning that became required reading at the school. He was promoted, ahead of his peers, to become a colonel and then a general. On the way, Taguba earned three master's degrees - in public administration, international relations, and national-security studies.

"I'll talk to you about discrimination," he said one morning, while discussing, without bitterness, his early years as an Army officer. "Let's talk about being refused to be served at a restaurant in public. Let's talk about having to do things two times, and being accused of not speaking English well, and having to pay myself for my three master's degrees because the Army didn't think I was smart enough. So what? Just work your ass off. So what? The hard work paid off."

Taguba had joined the Army knowing little about his father's military experience. "He saw the ravages and brutality of war, but he wasn't about to brag about his exploits," Taguba said. "He didn't say anything until 1997, and it took me two years to rebuild his records and show that he was authorized for an award." On Tomas's eightieth birthday, he was awarded the Bronze Star and a prisoner-of-war medal in a ceremony at Schofield Barracks, in Hawaii. "My father never laughed," Taguba said. But the day he got his medal "he smiled - he had a big-ass smile on his face. I'd never seen him look so proud. He was a bent man with carpal-tunnel syndrome, but at the end of the medal ceremony he stood himself up and saluted. I cried, and everyone in my family burst into tears."

Richard Armitage, a former Navy counter-insurgency officer who served as Deputy Secretary of State in the first Bush term, recalled meeting Taguba, then a lieutenant colonel, in South Korea in the early nineteen-nineties. "I was told to keep an eye on this young guy - 'He's going to be a general,' " Armitage said. "Taguba was discreet and low key - not a sprinter but a marathoner."

At the time, Taguba was working for Major General Mike Myatt, a marine who was the officer in charge of strategic talks with the South Koreans, on behalf of the American military. "I needed an executive assistant with brains and integrity," Myatt, who is now retired and living in San Francisco, told me. After interviewing a number of young officers, he chose Taguba. "He was ethical and he knew his stuff," Myatt said. "We really became close, and I'd trust him with my life. We talked about military strategy and policy, and the moral aspect of war - the importance of not losing the moral high ground." Myatt followed Taguba's involvement in the Abu Ghraib inquiry, and said, "I was so proud of him. I told him, 'Tony, you've maintained yourself, and your integrity.' "

Taguba got a different message, however, from other officers, among them General John Abizaid, then the head of Central Command. A few weeks after his report became public, Taguba, who was still in Kuwait, was in the back seat of a Mercedes sedan with Abizaid. Abizaid's driver and his interpreter, who also served as a bodyguard, were in front. Abizaid turned to Taguba and issued a quiet warning: "You and your report will be investigated."

"I wasn't angry about what he said but disappointed that he would say that to me," Taguba said. "I'd been in the Army thirty-two years by then, and it was the first time that I thought I was in the Mafia."

The Investigation

Taguba was given the job of investigating Abu Ghraib because of circumstance: the senior officer of the 800th Military Police Brigade, to which the soldiers in the photographs belonged, was a one-star general; Army regulations required that the head of the inquiry be senior to the commander of the unit being investigated, and Taguba, a two-star general, was available. "It was as simple as that," he said. He vividly remembers his first thought upon seeing the photographs in late January of 2004: "Unbelievable! What were these people doing?" There was an immediate second thought: "This is big."

Taguba decided to keep the photographs from most of the interrogators and researchers on his staff of twenty-three officers. "I didn't want them to prejudge the soldiers they were investigating, so I put the photos in a safe," he told me. "Anyone who wanted to see them had to have a need-to-know and go through me." His decision to keep the staff in the background was also intended to insure that none of them suffered damage to his or her career because of involvement in the inquiry. "I knew it was going to be very sensitive because of the gravity of what was in front of us," he said.

The team spent much of February, 2004, in Iraq. Taguba was overwhelmed by the scale of the wrongdoing. "These were people who were taken off the streets and put in jail - teen-agers and old men and women," he said. "I kept on asking these questions of the officers I interviewed: 'You knew what was going on. Why didn't you do something to stop it?' "

Taguba's assignment was limited to investigating the 800th M.P.s, but he quickly found signs of the involvement of military intelligence - both the 205th Military Intelligence Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas Pappas, which worked closely with the M.P.s, and what were called "other government agencies," or O.G.A.s, a euphemism for the C.I.A. and special-operations units operating undercover in Iraq. Some of the earliest evidence involved Lieutenant Colonel Steven L. Jordan, whose name was mentioned in interviews with several M.P.s. For the first three weeks of the investigation, Jordan was nowhere to be found, despite repeated requests. When the investigators finally located him, he asked whether he needed to shave his beard before being interviewed - Taguba suspected that he had been dressing as a civilian. "When I asked him about his assignment, he says, 'I'm a liaison officer for intelligence from Army headquarters in Iraq.' " But in the course of three or four interviews with Jordan, Taguba said, he began to suspect that the lieutenant colonel had been more intimately involved in the interrogation process - some of it brutal - for "high value" detainees.

"Jordan denied everything, and yet he had the authority to enter the prison's 'hard site' " - where the most important detainees were held - "carrying a carbine and an M9 pistol, which is against regulations," Taguba said. Jordan had also led a squad of military policemen in a shoot-out inside the hard site with a detainee from Syria who had managed to obtain a gun. (A lawyer for Jordan disputed these allegations; in the shoot-out, he said, Jordan was "just another gun on the extraction team" and not the leader. He noted that Jordan was not a trained interrogator.)

Taguba said that Jordan's "record reflected an extensive intelligence background." He also had reason to believe that Jordan was not reporting through the chain of command. But Taguba's narrowly focussed mission constrained the questions he could ask. "I suspected that somebody was giving them guidance, but I could not print that," Taguba said.

"After all Jordan's evasiveness and misleading responses, his rights were read to him," Taguba went on. Jordan subsequently became the only officer facing trial on criminal charges in connection with Abu Ghraib and is scheduled to be court-martialled in late August. (Seven M.P.s were convicted of charges that included dereliction of duty, maltreatment, and assault; one defendant, Specialist Charles Graner, was sentenced to ten years in prison.) Last month, a military judge ruled that Jordan, who is still assigned to the Army's Intelligence and Security Command, had not been appropriately advised of his rights during his interviews with Taguba, undermining the Army's allegation that he lied during the Taguba inquiry. Six other charges remain, including failure to obey an order or regulation; cruelty and maltreatment; and false swearing and obstruction of justice. (His lawyer said, "The evidence clearly shows that he is innocent.")

Taguba came to believe that Lieutenant General Sanchez, the Army commander in Iraq, and some of the generals assigned to the military headquarters in Baghdad had extensive knowledge of the abuse of prisoners in Abu Ghraib even before Joseph Darby came forward with the CD. Taguba was aware that in the fall of 2003 - when much of the abuse took place - Sanchez routinely visited the prison, and witnessed at least one interrogation. According to Taguba, "Sanchez knew exactly what was going on."

Taguba learned that in August, 2003, as the Sunni insurgency in Iraq was gaining force, the Pentagon had ordered Major General Geoffrey Miller, the commander at Guantánamo, to Iraq. His mission was to survey the prison system there and to find ways to improve the flow of intelligence. The core of Miller's recommendations, as summarized in the Taguba report, was that the military police at Abu Ghraib should become part of the interrogation process: they should work closely with interrogators and intelligence officers in "setting the conditions for successful exploitation of the internees."

Taguba concluded that Miller's approach was not consistent with Army doctrine, which gave military police the overriding mission of making sure that the prisons were secure and orderly. His report cited testimony that interrogators and other intelligence personnel were encouraging the abuse of detainees. "Loosen this guy up for us," one M.P. said he was told by a member of military intelligence. "Make sure he has a bad night."

The M.P.s, Taguba said, "were being literally exploited by the military interrogators. My view is that those kids" - even the soldiers in the photographs - "were poorly led, not trained, and had not been given any standard operating procedures on how they should guard the detainees."

Surprisingly, given Taguba's findings, Miller was the officer chosen to restore order at Abu Ghraib. In April, 2004, a month after the report was filed, he was reassigned there as the deputy commander for detainee operations. "Miller called in the spring and asked to meet with me to discuss Abu Ghraib, but I waited for him and we never did meet," Taguba recounted. Miller later told Taguba that he'd been ordered to Washington to meet with Rumsfeld before travelling to Iraq, but he never attempted to reschedule the meeting.

If they had spoken, Taguba said, he would have reminded Miller that at Abu Ghraib, unlike at Guantánamo, very few prisoners were affiliated with any terrorist group. Taguba had seen classified documents revealing that there were only "one or two" suspected Al Qaeda prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Most of the detainees had nothing to do with the insurgency. A few of them were common criminals.

Taguba had known Miller for years. "We served together in Korea and in the Pentagon, and his wife and mine used to go shopping together," Taguba said. But, after his report became public, "Miller didn't talk to me. He didn't say a word when I passed him in the hallway."

Despite the subsequent public furor over Abu Ghraib, neither the House nor the Senate Armed Services Committee hearings led to a serious effort to determine whether the scandal was a result of a high-level interrogation policy that encouraged abuse. At the House Committee hearing on May 7, 2004, a freshman Democratic congressman, Kendrick Meek, of Florida, asked Rumsfeld if it was time for him to resign. Rumsfeld replied, "I would resign in a minute if I thought that I couldn't be effective... . I have to wrestle with that." But, he added, "I'm certainly not going to resign because some people are trying to make a political issue out of it." (Rumsfeld stayed in office for the next two and a half years, until the day after the 2006 congressional elections.) When I spoke to Meek recently, he said, "There was no way Rumsfeld didn't know what was going on. He's a guy who wants to know everything, and what he was giving us was hard to believe."

Later that month, Rumsfeld appeared before a closed hearing of the House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, which votes on the funds for all secret operations in the military. Representative David Obey, of Wisconsin, the senior Democrat at the hearing, told me that he had been angry when a fellow subcommittee member "made the comment that 'Abu Ghraib was the price of defending democracy.' I said that wasn't the way I saw it, and that I didn't want to see some corporal made into a scapegoat. This could not have happened without people in the upper echelon of the Administration giving signals. I just didn't see how this was not systemic."

Obey asked Rumsfeld a series of pointed questions. Taguba attended the closed hearing with Rumsfeld and recalled him bristling at Obey's inquiries. "I don't know what happened!" Rumsfeld told Obey. "Maybe you want to ask General Taguba."

Taguba got a chance to answer questions on May 11th, when he was summoned to appear before the Senate Armed Services Committee. Under-Secretary Stephen Cambone sat beside him. (Cambone was Rumsfeld's point man on interrogation policy.) Cambone, too, told the committee that he hadn't known about the specific abuses at Abu Ghraib until he saw Taguba's report, "when I was exposed to some of those photographs."

Carl Levin, Democrat of Michigan, tried to focus on whether Abu Ghraib was the consequence of a larger detainee policy. "These acts of abuse were not the spontaneous actions of lower-ranking enlisted personnel," Levin said. "These attempts to extract information from prisoners by abusive and degrading methods were clearly planned and suggested by others." The senators repeatedly asked about General Miller's trip to Iraq in 2003. Did the "Gitmo-izing" of Abu Ghraib - especially the model of using the M.P.s in "setting the conditions" for interrogations - lead to the abuses?

Cambone confirmed that Miller had been sent to Iraq with his approval, but insisted that the senators were "misreading General Miller's intent." Questioned on that point by Senator Jack Reed, Democrat of Rhode Island, Cambone said, "I don't know that I was being told, and I don't know that General Miller said that there should be that kind of activity that you are ascribing to his recommendation."

Reed then asked Taguba, "Was it clear from your reading of the [Miller] report that one of the major recommendations was to use guards to condition these prisoners?" Taguba replied, "Yes, sir. That was recommended on the report."

At another point, after Taguba confirmed that military intelligence had taken control of the M.P.s following Miller's visit, Levin questioned Cambone:

Taguba, looking back on his testimony, said, "That's the reason I wasn't in their camp - because I kept on contradicting them. I wasn't about to lie to the committee. I knew I was already in a losing proposition. If I lie, I lose. And, if I tell the truth, I lose."

Taguba had been scheduled to rotate to the Third Army's headquarters, at Fort McPherson, Georgia, in June of 2004. He was instead ordered back to the Pentagon, to work in the office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs. "It was a lateral assignment," Taguba said, with a smile and a shrug. "I didn't quibble. If you're going to do that to me, well, O.K. We all serve at the pleasure of the President." A retired four-star Army general later told Taguba that he had been sent to the job in the Pentagon so that he could "be watched." Taguba realized that his career was at a dead end.

Later in 2004, Taguba encountered Rumsfeld and one of his senior press aides, Lawrence Di Rita, in the Pentagon Athletic Center. Taguba was getting dressed after a workout. "I was tying my shoes," Taguba recalled. "I looked up, and there they were." Rumsfeld, who was putting his clothes into a locker, recognized Taguba and said, "Hello, General." Di Rita, who was standing beside Rumsfeld, said sarcastically, "See what you started, General? See what you started?"

Di Rita, who is now an official with Bank of America, recalled running into Taguba in the locker room but not his words. "Sounds like my brand of humor," he said, in an e-mail. "A comment like that would have been in an attempt to lighten the mood for General Taguba." (Di Rita added that Taguba had "my personal respect and admiration" and that of Rumsfeld. "He did a terrific job under difficult circumstances.") However, Taguba was troubled by the encounter, and later told a colleague, "I'm now the problem."

Deniability

A dozen government investigations have been conducted into Abu Ghraib and detainee abuse. A few of them picked up on matters raised by Taguba's report, but none followed through on the question of ultimate responsibility. Military investigators were precluded from looking into the role of Rumsfeld and other civilian leaders in the Pentagon; the result was that none found any high-level intelligence involvement in the abuse.

An independent panel headed by James R. Schlesinger, a former Secretary of Defense, did conclude that there was "institutional and personal responsibility at higher levels" for Abu Ghraib, but cleared Rumsfeld of any direct responsibility. In an August, 2004, report, the Schlesinger panel endorsed Rumsfeld's complaints, citing "the reluctance to move bad news up the chain of command" as the most important factor in Washington's failure to understand the significance of Abu Ghraib. "Given the magnitude of this problem, the Secretary of Defense and other senior DoD officials need a more effective information pipeline to inform them of high-profile incidents," the report said. Schlesinger and his colleagues apparently were unaware of the early e-mail messages that had informed the Pentagon of Abu Ghraib.

The official inquiries consistently provided the public with less information about abuses than outside studies conducted by human-rights groups. In one case, in November, 2004, an Army investigation, by Brigadier General Richard Formica, into the treatment of detainees at Camp Nama, a Special Forces detention center at Baghdad International Airport, concluded that detainees who reported being sodomized or beaten were seeking sympathy and better treatment, and thus were not credible. For example, Army doctors had initially noted that a complaining detainee's wounds were "consistent with the history [of abuse] he provided... . The doctor did find scars on his wrists and noted what he believed to be an anal fissure." Formica had the detainee reëxamined two days later, by another doctor, who found "no fissure, and no scarring... . As a result, I did not find medical evidence of the sodomy." In the case of a detainee who died in custody, Formica noted that there had been bruising to the "shoulders, chest, hip, and knees" but added, "It is not unusual for detainees to have minor bruising, cuts and scrapes." In July, 2006, however, Human Rights Watch issued a fifty-three-page report on the "serious mistreatment" of detainees at Camp Nama and two other sites, largely based on witness accounts from Special Forces interrogators and others who served there.

Formica, asked to comment, wrote in an e-mail, "I conducted a thorough investigation ... and stand by my report." He said that "several issues" he discovered "were corrected." His assignment, Formica noted, was to investigate a unit, and not to conduct "a systematic analysis of Special Operations activities."

The Army also protected General Miller. Since 2002, F.B.I. agents at Guantánamo had been telling their superiors that their military counterparts were abusing detainees. The F.B.I. complaints were ignored until after Abu Ghraib. When an investigation was opened, in December, 2004, General Craddock, Rumsfeld's former military aide, was in charge of the Army's Southern Command, with jurisdiction over Guantánamo - he had been promoted a few months after Taguba's visit to Rumsfeld's office. Craddock appointed Air Force Lieutenant General Randall M. Schmidt, a straight-talking fighter pilot, to investigate the charges, which included alleged abuses during Miller's tenure.

"I followed the bread-crumb trail," Schmidt, who retired last year, told me. "I found some things that didn't seem right. For lack of a camera, you could have seen in Guantánamo what was seen at Abu Ghraib."

Schmidt found that Miller, with the encouragement of Rumsfeld, had focussed great attention on the interrogation of Mohammed al-Qahtani, a Saudi who was believed to be the so-called "twentieth hijacker." Qahtani was interrogated "for twenty hours a day for at least fifty-four days," Schmidt told investigators from the Army Inspector General's office, who were reviewing his findings. "I mean, here's this guy manacled, chained down, dogs brought in, put in his face, told to growl, show teeth, and that kind of stuff. And you can imagine the fear."

At Guantánamo, Schmidt told the investigators, Miller "was responsible for the conduct of interrogations that I found to be abusive and degrading. The intent of those might have been to be abusive and degrading to get the information they needed... . Did the means justify the ends? That's fine... . He was responsible."

Schmidt formally recommended that Miller be "held accountable" and "admonished." Craddock rejected this recommendation and absolved Miller of any responsibility for the mistreatment of the prisoners. The Inspector General inquiry endorsed Craddock's action. "I was open with them," Schmidt told me, referring to the I.G. investigators. "I told them, 'I'll do anything to help you get the truth.' " But when he read their final report, he said, "I didn't recognize the five hours of interviews with me."

Schmidt learned of Craddock's reversal the day before they were to meet with Rumsfeld, in July, 2005. Rumsfeld was in frequent contact with Miller about the progress of Qahtani's interrogation, and personally approved the most severe interrogation tactics. ("This wasn't just daily business, when the Secretary of Defense is personally involved," Schmidt told the Army investigators.) Nonetheless, Schmidt was impressed by Rumsfeld's demonstrative surprise, dismay, and concern upon being told of the abuse. "He was going, 'My God! Did I authorize putting a bra and underwear on this guy's head and telling him all his buddies knew he was a homosexual?' "

Schmidt was convinced. "I got to tell you that I never got the feeling that Secretary Rumsfeld was trying to hide anything," he told me. "He got very frustrated. He's a control guy, and this had gotten out of control. He got pissed."

Rumsfeld's response to Schmidt was similar to his expressed surprise over Taguba's Abu Ghraib report. "Rummy did what we called 'case law' policy - verbal and not in writing," Taguba said. "What he's really saying is that if this decision comes back to haunt me I'll deny it."

Taguba eventually concluded that there was a reason for the evasions and stonewalling by Rumsfeld and his aides. At the time he filed his report, in March of 2004, Taguba said, "I knew there was C.I.A. involvement, but I was oblivious of what else was happening" in terms of covert military-intelligence operations. Later that summer, however, he learned that the C.I.A. had serious concerns about the abusive interrogation techniques that military-intelligence operatives were using on high-value detainees. In one secret memorandum, dated June 2, 2003, General George Casey, Jr., then the director of the Joint Staff in the Pentagon, issued a warning to General Michael DeLong, at the Central Command:

The Task Forces

Abu Ghraib had opened the door on the issue of the treatment of detainees, and from the beginning the Administration feared that the publicity would expose more secret operations and practices. Shortly after September 11th, Rumsfeld, with the support of President Bush, had set up military task forces whose main target was the senior leadership of Al Qaeda. Their essential tactic was seizing and interrogating terrorists and suspected terrorists; they also had authority from the President to kill certain high-value targets on sight. The most secret task-force operations were categorized as Special Access Programs, or S.A.P.s.

The military task forces were under the control of the Joint Special Operations Command, the branch of the Special Operations Command that is responsible for counterterrorism. One of Miller's unacknowledged missions had been to bring the J.S.O.C.'s "strategic interrogation" techniques to Abu Ghraib. In special cases, the task forces could bypass the chain of command and deal directly with Rumsfeld's office. A former senior intelligence official told me that the White House was also briefed on task-force operations.

The former senior intelligence official said that when the images of Abu Ghraib were published, there were some in the Pentagon and the White House who "didn't think the photographs were that bad" - in that they put the focus on enlisted soldiers, rather than on secret task-force operations. Referring to the task-force members, he said, "Guys on the inside ask me, 'What's the difference between shooting a guy on the street, or in his bed, or in a prison?' " A Pentagon consultant on the war on terror also said that the "basic strategy was 'prosecute the kids in the photographs but protect the big picture.' "

A recently retired C.I.A. officer, who served more than fifteen years in the clandestine service, told me that the task-force teams "had full authority to whack - to go in and conduct 'executive action,' " the phrase for political assassination. "It was surrealistic what these guys were doing," the retired operative added. "They were running around the world without clearing their operations with the ambassador or the chief of station."

J.S.O.C.'s special status undermined military discipline. Richard Armitage, the former Deputy Secretary of State, told me that, on his visits to Iraq, he increasingly found that "the commanders would say one thing and the guys in the field would say, 'I don't care what he says. I'm going to do what I want.' We've sacrificed the chain of command to the notion of Special Operations and GWOT" - the global war on terrorism. "You're painting on a canvas so big that it's hard to comprehend," Armitage said.

Thomas W. O'Connell, who resigned this spring after nearly four years as the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict, defended the task forces. He blamed the criticisms on the resentment of the rest of the military: "From my observation, the operations run by Special Ops units are extraordinarily open in terms of interagency visibility to embassies and C.I.A. stations - even to the point where there's been a question of security." O'Connell said that he dropped in unannounced to Special Operations interrogation centers in Iraq, "and the treatment of detainees was aboveboard." He added, "If people want to say we've got a serious problem with Special Operations, let them say it on the record."

Representative Obey told me that he had been troubled, before the Iraq war, by the Administration's decision to run clandestine operations from the Pentagon, saying that he "found some of the things they were doing to be disquieting." At the time, his Republican colleagues blocked his attempts to have the House Appropriations Committee investigate these activities. "One of the things that bugs me is that Congress has failed in its oversight abilities," Obey said. Early last year, at his urging, his subcommittee began demanding a classified quarterly report on the operations, but Obey said that he has no reason to believe that the reports are complete.

A former high-level Defense Department official said that, when the Abu Ghraib scandal broke, Senator John Warner, then the chairman of the Armed Services Committee, was warned "to back off" on the investigation, because "it would spill over to more important things." A spokesman for Warner acknowledged that there had been pressure on the Senator, but said that Warner had stood up to it - insisting on putting Rumsfeld under oath for his May 7th testimony, for example, to the Secretary's great displeasure.

An aggressive congressional inquiry into Abu Ghraib could have provoked unwanted questions about what the Pentagon was doing, in Iraq and elsewhere, and under what authority. By law, the President must make a formal finding authorizing a C.I.A. covert operation, and inform the senior leadership of the House and the Senate Intelligence Committees. However, the Bush Administration unilaterally determined after 9/11 that intelligence operations conducted by the military - including the Pentagon's covert task forces - for the purposes of "preparing the battlefield" could be authorized by the President, as Commander-in-Chief, without telling Congress.

There was coördination between the C.I.A. and the task forces, but also tension. The C.I.A. officers, who were under pressure to produce better intelligence in the field, wanted explicit legal authority before aggressively interrogating high-value targets. A finding would give operatives some legal protection for questionable actions, but the White House was reluctant to put what it wanted in writing.

A recently retired high-level C.I.A. official, who served during this period and was involved in the drafting of findings, described to me the bitter disagreements between the White House and the agency over the issue. "The problem is what constituted approval," the retired C.I.A. official said. "My people fought about this all the time. Why should we put our people on the firing line somewhere down the road? If you want me to kill Joe Smith, just tell me to kill Joe Smith. If I was the Vice-President or the President, I'd say, 'This guy Smith is a bad guy and it's in the interest of the United States for this guy to be killed.' They don't say that. Instead, George" - George Tenet, the director of the C.I.A. until mid-2004 - "goes to the White House and is told, 'You guys are professionals. You know how important it is. We know you'll get the intelligence.' George would come back and say to us, 'Do what you gotta do.' "

Bill Harlow, a spokesman for Tenet, depicted as "absurd" the notion that the C.I.A. director told his agents to operate outside official guidelines. He added, in an e-mailed statement, "The intelligence community insists that its officers not exceed the very explicit authorities granted." In his recently published memoir, however, Tenet acknowledged that there had been a struggle "to get clear guidance" in terms of how far to go during high-value-detainee interrogations.

The Pentagon consultant said in an interview late last year that "the C.I.A. never got the exact language it wanted." The findings, when promulgated by the White House, were "very calibrated" to minimize political risk, and limited to a few countries; later, they were expanded, turning several nations in North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia into free-fire zones with regard to high-value targets. I was told by the former senior intelligence official and a government consultant that after the existence of secret C.I.A. prisons in Europe was revealed, in the Washington Post, in late 2005, the Administration responded with a new detainee center in Mauritania. After a new government friendly to the U.S. took power, in a bloodless coup d'état in August, 2005, they said, it was much easier for the intelligence community to mask secret flights there.

"The dirt and secrets are in the back channel," the former senior intelligence officer noted. "All this open business - sitting in staff meetings, etc., etc. - is the Potemkin Village stuff. And the good guys - like Taguba - are gone."

In some cases, the secret operations remained unaccountable. In an April, 2005, memorandum, a C.I.D. officer - his name was redacted - complained to C.I.D. headquarters, at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, about the impossibility of investigating military members of a Special Access Program suspected of prisoner abuse:

The C.I.D. officer wrote that "fake names were used" by members of the task force; he also told investigators that the unit had a "major computer malfunction which resulted in them losing 70 per cent of their files; therefore, they can't find the cases we need to review."

The officer concluded that the investigation "does not need to be reopened. Hell, even if we reopened it we wouldn't get any more information than we already have."

Consequences

Rumsfeld was vague, in his appearances before Congress, about when he had informed the President about Abu Ghraib, saying that it could have been late January or early February. He explained that he routinely met with the President "once or twice a week ... and I don't keep notes about what I do." He did remember that in mid-March he and General Myers were "meeting with the President and discussed the reports that we had obviously heard" about Abu Ghraib.

Whether the President was told about Abu Ghraib in January (when e-mails informed the Pentagon of the seriousness of the abuses and of the existence of photographs) or in March (when Taguba filed his report), Bush made no known effort to forcefully address the treatment of prisoners before the scandal became public, or to reëvaluate the training of military police and interrogators, or the practices of the task forces that he had authorized. Instead, Bush acquiesced in the prosecution of a few lower-level soldiers. The President's failure to act decisively resonated through the military chain of command: aggressive prosecution of crimes against detainees was not conducive to a successful career.

In January of 2006, Taguba received a telephone call from General Richard Cody, the Army's Vice-Chief of Staff. "This is your Vice," he told Taguba. "I need you to retire by January of 2007." No pleasantries were exchanged, although the two generals had known each other for years, and, Taguba said, "He offered no reason." (A spokesperson for Cody said, "Conversations regarding general officer management are considered private personnel discussions. General Cody has great respect for Major General Taguba as an officer, leader, and American patriot.")

"They always shoot the messenger," Taguba told me. "To be accused of being overzealous and disloyal - that cuts deep into me. I was being ostracized for doing what I was asked to do."

Taguba went on, "There was no doubt in my mind that this stuff" - the explicit images - "was gravitating upward. It was standard operating procedure to assume that this had to go higher. The President had to be aware of this." He said that Rumsfeld, his senior aides, and the high-ranking generals and admirals who stood with him as he misrepresented what he knew about Abu Ghraib had failed the nation.

"From the moment a soldier enlists, we inculcate loyalty, duty, honor, integrity, and selfless service," Taguba said. "And yet when we get to the senior-officer level we forget those values. I know that my peers in the Army will be mad at me for speaking out, but the fact is that we violated the laws of land warfare in Abu Ghraib. We violated the tenets of the Geneva Convention. We violated our own principles and we violated the core of our military values. The stress of combat is not an excuse, and I believe, even today, that those civilian and military leaders responsible should be held accountable." ?

|

|

Torture "widespread" under U.S. custody: Amnesty

By Richard Waddington Wed May 3, 1:07 AM ET Torture and inhumane treatment are "widespread" in U.S.-run detention centers in Afghanistan, Iraq, Cuba and elsewhere despite Washington's denials, Amnesty International said on Wednesday. In a report for the United Nations' Committee against Torture, the London-based human rights group also alleged abuses within the U.S. domestic law enforcement system, including use of excessive force by police and degrading conditions of isolation for inmates in high security prisons. "Evidence continues to emerge of widespread torture and other cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment of detainees held in U.S. custody," Amnesty said in its 47-page report. It said that while Washington has sought to blame abuses that have recently come to light on "aberrant soldiers and lack of oversight," much ill-treatment stemmed from officially sanctioned interrogation procedures and techniques. "The U.S. government is not only failing to take steps to eradicate torture, it is actually creating a climate in which torture and other ill-treatment can flourish," said Amnesty International USA Senior Deputy Director-General Curt Goering. The U.N. committee, whose experts carry out periodic reviews of countries signatory to the U.N. Convention against Torture, is scheduled to begin consideration of the United States on Friday. The last U.S. review was in 2000. It said in November it was seeking U.S. answers to questions including whether Washington operated secret detention centers abroad and whether President George W. Bush had the power to absolve anyone from criminal responsibility in torture cases. The committee also wanted to know whether a December 2004 memorandum from the U.S. Attorney General's office, reserving torture for "extreme" acts of cruelty, was compatible with the global convention barring all forms of cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment. UNTIL THE END "Like other wars, when they start, we do not know when they will end. Still, we may detain combatants until the end of the war," it said. The U.S. human rights image has taken a battering abroad over a string of scandals involving the sexual and physical abuse of detainees held by American forces in Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo Bay. In its submission, Washington did not mention alleged secret detention centers. Amnesty listed a series of incidents in recent years involving torture of detainees in U.S. custody, noting the heaviest sentence given to perpetrators was five months in jail. This was the same punishment you could get for stealing a bicycle in the United States, it added. "Although the U.S. government continues to assert its condemnation of torture and ill-treatment, these statements contradict what is happening in practice," said Goering, referring to the testimony of torture victims in the report. |

|

January 23, 2006 Verdict:

Army Chief Warrant Officer Lewis Welshofer Jr., who was convicted of negligent homicide

and dereliction of duty in the interrogation death of an Iraqi general, came in for

only a reprimand Monday.

FORT CARSON, CO Jan. 22, 2006 (AP) |

|

Return My Work, Says Guantánamo Poet

Declan Walsh in Peshawar

The Americans can't return the three years that Abdul Rahim Muslim Dost lost, locked in a

cell in Guantánamo Bay. But they could at least give back his poetry.

"Please help," said Dost, who says he penned 25,000 lines of verse during his long

imprisonment. "Those words are very precious to me. My interrogators promised I would get

them back. Still I have nothing."

The lost poems are the final indignity for Dost, a softly spoken Afghan whom the US military

flew home last year, finally believing his pleas of innocence.

Accused of being an al-Qaida terrorist, Dost had been whisked from his home in Peshawar,

northern Pakistan, in November 2001. Five months later he was shackled, blindfolded and

flown to Cuba. Wearing an orange jumpsuit and trapped inside a mesh cage, the Pashtun poet

crafted his escape through verse. "I would fly on the wings of my imagination," he recalled.

"Through my poems I would travel the world, visiting different places. Although I was in a

cage I was really free."

Inmates were forbidden pens or papers during Dost's first year in captivity. So he found a

novel solution - polystyrene teacups. "I would scratch a few lines on to a cup with a spoon.

If you held it up to the light you could read it," he said. "But when the guards collected

the trash they threw them away."

It was only when prison authorities provided awkward rubbery pens - so soft they could

not be used as weapons - that Dost wrote in earnest. His themes were love of his homeland,

poetry and his children, and especially his hope of release.

Sitting in his library, he quoted a couplet from a favourite poem: "Handcuffs befit

brave young men/Bangles are for spinsters or pretty young ladies."

Dost lampooned his military captors, mocking what he perceived as ridiculous - women with

men's haircuts, men without beards. "In the American army I could not see a real man,"

he said. "And they talk rudely about homosexuals, which is very shameful to us."

The satires delighted fellow inmates, who passed them from cage to cage using a pulley

system fashioned from prayer cap threads. Some even passed Dost their two-sheet paper

allowance so he could write some more. But invariably the poems were confiscated during

cell searches. Early last year Dost was brought before a military tribunal - which he

describes as a show trial - and then flown back to Afghanistan in shackles, with 16

other detainees. The US military said he was "no longer an enemy combatant". Dost was

allowed to keep his final sheaf of poems and was told the rest would be returned on

arrival at Bagram airbase, near Kabul. But they were not, and he was set free without

apology or compensation. His brother had been freed six months earlier.

Now Dost has written his an account of Guantánamo, The Broken Chains, which

is being translated into English. He estimates $300,000 in losses, mostly from

confiscated gemstones and cash that were never returned. But his greatest loss was

his writing. "It is the most valuable thing to me," he said.

|

|

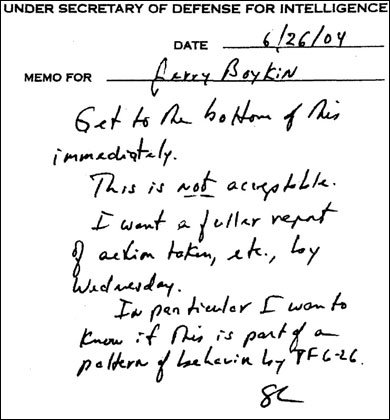

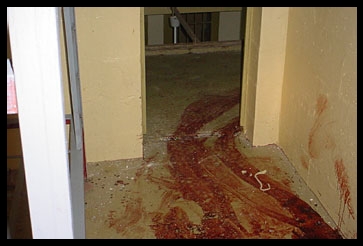

In Secret Unit's 'Black Room,' a Grim Portrait of U.S. Abuse

By Eric Schmitt and Carolyn Marshall

As the Iraqi insurgency intensified in early 2004, an elite Special Operations forces unit converted one of Saddam Hussein's former military bases near Baghdad into a top-secret detention center. There, American soldiers made one of the former Iraqi government's torture chambers into their own interrogation cell. They named it the Black Room. In the windowless, jet-black garage-size room, some soldiers beat prisoners with rifle butts, yelled and spit in their faces and, in a nearby area, used detainees for target practice in a game of jailer paintball. Their intention was to extract information to help hunt down Iraq's most-wanted terrorist, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, according to Defense Department personnel who served with the unit or were briefed on its operations. The Black Room was part of a temporary detention site at Camp Nama, the secret headquarters of a shadowy military unit known as Task Force 6-26. Located at Baghdad International Airport, the camp was the first stop for many insurgents on their way to the Abu Ghraib prison a few miles away. Placards posted by soldiers at the detention area advised, "NO BLOOD, NO FOUL." The slogan, as one Defense Department official explained, reflected an adage adopted by Task Force 6-26: "If you don't make them bleed, they can't prosecute for it." According to Pentagon specialists who worked with the unit, prisoners at Camp Nama often disappeared into a detention black hole, barred from access to lawyers or relatives, and confined for weeks without charges. "The reality is, there were no rules there," another Pentagon official said. The story of detainee abuse in Iraq is a familiar one. But the following account of Task Force 6-26, based on documents and interviews with more than a dozen people, offers the first detailed description of how the military's most highly trained counterterrorism unit committed serious abuses. It adds to the picture of harsh interrogation practices at American military prisons in Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, as well as at secret Central Intelligence Agency detention centers around the world. The new account reveals the extent to which the unit members mistreated prisoners months before and after the photographs of abuse from Abu Ghraib were made public in April 2004, and it helps belie the original Pentagon assertions that abuse was confined to a small number of rogue reservists at Abu Ghraib. The abuses at Camp Nama continued despite warnings beginning in August 2003 from an Army investigator and American intelligence and law enforcement officials in Iraq. The C.I.A. was concerned enough to bar its personnel from Camp Nama that August. It is difficult to compare the conditions at the camp with those at Abu Ghraib because so little is known about the secret compound, which was off limits even to the Red Cross. The abuses appeared to have been unsanctioned, but some of them seemed to have been well known throughout the camp. For an elite unit with roughly 1,000 people at any given time, Task Force 6-26 seems to have had a large number of troops punished for detainee abuse. Since 2003, 34 task force members have been disciplined in some form for mistreating prisoners, and at least 11 members have been removed from the unit, according to new figures the Special Operations Command provided in response to questions from The New York Times. Five Army Rangers in the unit were convicted three months ago for kicking and punching three detainees in September 2005. Some of the serious accusations against Task Force 6-26 have been reported over the past 16 months by news organizations including NBC, The Washington Post and The Times. Many details emerged in hundreds of pages of documents released under a Freedom of Information Act request by the American Civil Liberties Union. But taken together for the first time, the declassified documents and interviews with more than a dozen military and civilian Defense Department and other federal personnel provide the most detailed portrait yet of the secret camp and the inner workings of the clandestine unit. The documents and interviews also reflect a culture clash between the free-wheeling military commandos and the more cautious Pentagon civilians working with them that escalated to a tense confrontation. At one point, one of Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld's top aides, Stephen A. Cambone, ordered a subordinate to "get to the bottom" of any misconduct. Most of the people interviewed for this article were midlevel civilian and military Defense Department personnel who worked with Task Force 6-26 and said they witnessed abuses, or who were briefed on its operations over the past three years. Many were initially reluctant to discuss Task Force 6-26 because its missions are classified. But when pressed repeatedly by reporters who contacted them, they agreed to speak about their experiences and observations out of what they said was anger and disgust over the unit's treatment of detainees and the failure of task force commanders to punish misconduct more aggressively. The critics said the harsh interrogations yielded little information to help capture insurgents or save American lives. Virtually all of those who agreed to speak are career government employees, many with previous military service, and they were granted anonymity to encourage them to speak candidly without fear of retribution from the Pentagon. Many of their complaints are supported by declassified military documents and e-mail messages from F.B.I. agents who worked regularly with the task force in Iraq. A Demand for Intelligence Military officials say there may have been extenuating circumstances for some of the harsh treatment at Camp Nama and its field stations in other parts of Iraq. By the spring of 2004, the demand on interrogators for intelligence was growing to help combat the increasingly numerous and deadly insurgent attacks. Some detainees may have been injured resisting capture. A spokesman for the Special Operations Command, Kenneth S. McGraw, said there was sufficient evidence to prove misconduct in only 5 of 29 abuse allegations against task force members since 2003. As a result of those five incidents, 34 people were disciplined. "We take all those allegations seriously," Gen. Bryan D. Brown, the commander of the Special Operations Command, said in a brief hallway exchange on Capitol Hill on March 8. "Any kind of abuse is not consistent with the values of the Special Operations Command." The secrecy surrounding the highly classified unit has helped to shield its conduct from public scrutiny. The Pentagon will not disclose the unit's precise size, the names of its commanders, its operating bases or specific missions. Even the task force's name changes regularly to confuse adversaries, and the courts-martial and other disciplinary proceedings have not identified the soldiers in public announcements as task force members. General Brown's command declined requests for interviews with several former task force members and with Lt. Gen. Stanley McChrystal, who leads the Joint Special Operations Command, the headquarters at Fort Bragg, N.C., that supplies the unit's most elite troops. One Special Operations officer and a senior enlisted soldier identified by Defense Department personnel as former task force members at Camp Nama declined to comment when contacted by telephone. Attempts to contact three other Special Operations soldiers who were in the unit — by phone, through relatives and former neighbors — were also unsuccessful. Cases of detainee abuse attributed to Task Force 6-26 demonstrate both confusion over and, in some cases, disregard for approved interrogation practices and standards for detainee treatment, according to Defense Department specialists who have worked with the unit. In early 2004, an 18-year-old man suspected of selling cars to members of the Zarqawi terrorist network was seized with his entire family at their home in Baghdad. Task force soldiers beat him repeatedly with a rifle butt and punched him in the head and kidneys, said a Defense Department specialist briefed on the incident. Some complaints were ignored or played down in a unit where a conspiracy of silence contributed to the overall secretiveness. "It's under control," one unit commander told a Defense Department official who complained about mistreatment at Camp Nama in the spring of 2004. For hundreds of suspected insurgents, Camp Nama was a way station on a journey that started with their capture on the battlefield or in their homes, and ended often in a cell at Abu Ghraib. Hidden in plain sight just off a dusty road fronting Baghdad International Airport, Camp Nama was an unmarked, virtually unknown compound at the edge of the taxiways. The heart of the camp was the Battlefield Interrogation Facility, alternately known as the Temporary Detention Facility and the Temporary Holding Facility. The interrogation and detention areas occupied a corner of the larger compound, separated by a fence topped with razor wire. Unmarked helicopters flew detainees into the camp almost daily, former task force members said. Dressed in blue jumpsuits with taped goggles covering their eyes, the shackled prisoners were led into a screening room where they were registered and examined by medics. Just beyond the screening rooms, where Saddam Hussein was given a medical exam after his capture, detainees were kept in as many as 85 cells spread over two buildings. Some detainees were kept in what was known as Motel 6, a group of crudely built plywood shacks that reeked of urine and excrement. The shacks were cramped, forcing many prisoners to squat or crouch. Other detainees were housed inside a separate building in 6-by-8-foot cubicles in a cellblock called Hotel California. The interrogation rooms were stark. High-value detainees were questioned in the Black Room, nearly bare but for several 18-inch hooks that jutted from the ceiling, a grisly reminder of the terrors inflicted by Mr. Hussein's inquisitors. Jailers often blared rap music or rock 'n' roll at deafening decibels over a loudspeaker to unnerve their subjects. Another smaller room offered basic comforts like carpets and cushioned seating to put more cooperative prisoners at ease, said several Defense Department specialists who worked at Camp Nama. Detainees wore heavy, olive-drab hoods outside their cells. By June 2004, the revelations of abuse at Abu Ghraib galvanized the military to promise better treatment for prisoners. In one small concession at Camp Nama, soldiers exchanged the hoods for cloth blindfolds with drop veils that allowed detainees to breathe more freely but prevented them from peeking out. Some former task force members said the Nama in the camp's name stood for a coarse phrase that soldiers used to describe the compound. One Defense Department specialist recalled seeing pink blotches on detainees' clothing as well as red welts on their bodies, marks he learned later were inflicted by soldiers who used detainees as targets and called themselves the High Five Paintball Club. Mr. McGraw, the military spokesman, said he had not heard of the Black Room or the paintball club and had not seen any mention of them in the documents he had reviewed. In a nearby operations center, task force analysts pored over intelligence collected from spies, detainees and remotely piloted Predator surveillance aircraft, to piece together clues to aid soldiers on their raids. Twice daily at noon and midnight military interrogators and their supervisors met with officials from the C.I.A., F.B.I. and allied military units to review operations and new intelligence. Task Force 6-26 was a creation of the Pentagon's post-Sept. 11 campaign against terrorism, and it quickly became the model for how the military would gain intelligence and battle insurgents in the future. Originally known as Task Force 121, it was formed in the summer of 2003, when the military merged two existing Special Operations units, one hunting Osama bin Laden in and around Afghanistan, and the other tracking Mr. Hussein in Iraq. (Its current name is Task Force 145.) The task force was a melting pot of military and civilian units. It drew on elite troops from the Joint Special Operations Command, whose elements include the Army unit Delta Force, Navy's Seal Team 6 and the 75th Ranger Regiment. Military reservists and Defense Intelligence Agency personnel with special skills, like interrogators, were temporarily assigned to the unit. C.I.A. officers, F.B.I. agents and special operations forces from other countries also worked closely with the task force. Many of the American Special Operations soldiers wore civilian clothes and were allowed to grow beards and long hair, setting them apart from their uniformed colleagues. Unlike conventional soldiers and marines whose Iraq tours lasted 7 to 12 months, unit members and their commanders typically rotated every 90 days. Task Force 6-26 had a singular focus: capture or kill Mr. Zarqawi, the Jordanian militant operating in Iraq. "Anytime there was even the smell of Zarqawi nearby, they would go out and use any means possible to get information from a detainee," one official said. Defense Department personnel briefed on the unit's operations said the harsh treatment extended beyond Camp Nama to small field outposts in Baghdad, Falluja, Balad, Ramadi and Kirkuk. These stations were often nestled within the alleys of a city in nondescript buildings with suburban-size yards where helicopters could land to drop off or pick up detainees. At the outposts, some detainees were stripped naked and had cold water thrown on them to cause the sensation of drowning, said Defense Department personnel who served with the unit. In January 2004, the task force captured the son of one of Mr. Hussein's bodyguards in Tikrit. The man told Army investigators that he was forced to strip and that he was punched in the spine until he fainted, put in front of an air-conditioner while cold water was poured on him and kicked in the stomach until he vomited. Army investigators were forced to close their inquiry in June 2005 after they said task force members used battlefield pseudonyms that made it impossible to identify and locate the soldiers involved. The unit also asserted that 70 percent of its computer files had been lost. Despite the task force's access to a wide range of intelligence, its raids were often dry holes, yielding little if any intelligence and alienating ordinary Iraqis, Defense Department personnel said. Prisoners deemed no threat to American troops were often driven deep into the Iraqi desert at night and released, sometimes given $100 or more in American money for their trouble. Back at Camp Nama, the task force leaders established a ritual for departing personnel who did a good job, Pentagon officials said. The commanders presented them with two unusual mementos: a detainee hood and a souvenir piece of tile from the medical screening room that once held Mr. Hussein. Early Signs of Trouble Accusations of abuse by Task Force 6-26 came as no surprise to many other officials in Iraq. By early 2004, both the C.I.A. and the F.B.I. had expressed alarm about the military's harsh interrogation techniques. The C.I.A.'s Baghdad station sent a cable to headquarters on Aug. 3, 2003, raising concern that Special Operations troops who served with agency officers had used techniques that had become too aggressive. Five days later, the C.I.A. issued a classified directive that prohibited its officers from participating in harsh interrogations. Separately, the C.I.A. barred its officers from working at Camp Nama but allowed them to keep providing target information and other intelligence to the task force. The warnings still echoed nearly a year later. On June 25, 2004, nearly two months after the disclosure of the abuses at Abu Ghraib, an F.B.I. agent in Iraq sent an e-mail message to his superiors in Washington, warning that a detainee captured by Task Force 6-26 had suspicious burn marks on his body. The detainee said he had been tortured. A month earlier, another F.B.I. agent asked top bureau officials for guidance on how to deal with military interrogators across Iraq who used techniques like loud music and yelling that exceeded "the bounds of standard F.B.I. practice." American generals were also alerted to the problem. In December 2003, Col. Stuart A. Herrington, a retired Army intelligence officer, warned in a confidential memo that medical personnel reported that prisoners seized by the unit, then known as Task Force 121, had injuries consistent with beatings. "It seems clear that TF 121 needs to be reined in with respect to its treatment of detainees," Colonel Herrington concluded. By May 2004, just as the scandal at Abu Ghraib was breaking, tensions increased at Camp Nama between the Special Operations troops and civilian interrogators and case officers from the D.I.A.'s Defense Human Intelligence Service, who were there to support the unit in its fight against the Zarqawi network. The discord, according to documents, centered on the harsh treatment of detainees as well as restrictions the Special Operations troops placed on their civilian colleagues, like monitoring their e-mail messages and phone calls. Maj. Gen. George E. Ennis, who until recently commanded the D.I.A.'s human intelligence division, declined to be interviewed for this article. But in written responses to questions, General Ennis said he never heard about the numerous complaints made by D.I.A. personnel until he and his boss, Vice Adm. Lowell E. Jacoby, then the agency's director, were briefed on June 24, 2004. The next day, Admiral Jacoby wrote a two-page memo to Mr. Cambone, under secretary of defense for intelligence. In it, he described a series of complaints, including a May 2004 incident in which a D.I.A. interrogator said he witnessed task force soldiers punch a detainee hard enough to require medical help. The D.I.A. officer took photos of the injuries, but a supervisor confiscated them, the memo said. The tensions laid bare a clash of military cultures. Combat-hardened commandos seeking a steady flow of intelligence to pinpoint insurgents grew exasperated with civilian interrogators sent from Washington, many of whom were novices at interrogating hostile prisoners fresh off the battlefield. "These guys wanted results, and our debriefers were used to a civil environment," said one Defense Department official who was briefed on the task force operations. Within days after Admiral Jacoby sent his memo, the D.I.A. took the extraordinary step of temporarily withdrawing its personnel from Camp Nama. Admiral Jacoby's memo also provoked an angry reaction from Mr. Cambone. "Get to the bottom of this immediately. This is not acceptable," Mr. Cambone said in a handwritten note on June 26, 2004, to his top deputy, Lt. Gen. William G. Boykin. "In particular, I want to know if this is part of a pattern of behavior by TF 6-26." General Boykin said through a spokesman on March 17 that at the time he told Mr. Cambone he had found no pattern of misconduct with the task force. A Shroud of Secrecy Military and legal experts say the full breadth of abuses committed by Task Force 6-26 may never be known because of the secrecy surrounding the unit, and the likelihood that some allegations went unreported. In the summer of 2004, Camp Nama closed and the unit moved to a new headquarters in Balad, 45 miles north of Baghdad. The unit's operations are now shrouded in even tighter secrecy. Soon after their rank-and-file clashed in 2004, D.I.A. officials in Washington and military commanders at Fort Bragg agreed to improve how the task force integrated specialists into its ranks. The D.I.A. is now sending small teams of interrogators, debriefers and case officers, called "deployable Humint teams," to work with Special Operations forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. Senior military commanders insist that the elite warriors, who will be relied on more than ever in the campaign against terrorism, are now treating detainees more humanely and can police themselves. The C.I.A. has resumed conducting debriefings with the task force, but does not permit harsh questioning, a C.I.A. official said. General McChrystal, the leader of the Joint Special Operations Command, received his third star in a promotion ceremony at Fort Bragg on March 13. On Dec. 8, 2004, the Pentagon's spokesman, Lawrence Di Rita, said that four Special Operations soldiers from the task force were punished for "excessive use of force" and administering electric shocks to detainees with stun guns. Two of the soldiers were removed from the unit. To that point, Mr. Di Rita said, 10 task force members had been disciplined. Since then, according to the new figures provided to The Times, the number of those disciplined for detainee abuse has more than tripled. Nine of the 34 troops disciplined received written or oral counseling. Others were reprimanded for slapping detainees and other offenses. The five Army Rangers who were court-martialed in December received punishments including jail time of 30 days to six months and reduction in rank. Two of them will receive bad-conduct discharges upon completion of their sentences. Human rights advocates and leading members of Congress say the Pentagon must still do more to hold senior-level commanders and civilian officials accountable for the misconduct. The Justice Department inspector general is investigating complaints of detainee abuse by Task Force 6-26, a senior law enforcement official said. The only wide-ranging military inquiry into prisoner abuse by Special Operations forces was completed nearly a year ago by Brig. Gen. Richard P. Formica, and was sent to Congress. But the United States Central Command has refused repeated requests from The Times over the past several months to provide an unclassified copy of General Formica's findings despite Mr. Rumsfeld's instructions that such a version of all 12 major reports into detainee abuse be made public. E-mail: sfburo@nytimes.com. |

|

Tales of Torture, Horror From Prisoners at Gitmo