| “We don’t do [ Iraqi ] body counts.” |

IRAQ WAR CO$T

(JavaScript Error)

u.s. dead the coffins iraqi casualties |

|

|

"If we believe absurdities, we shall commit atrocities."

|

|

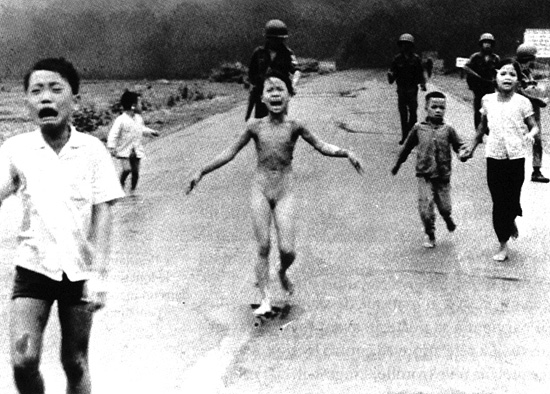

"The Way to Live is to Kill." Recalling Vietnam in 2003 |

AP APHUGH THOMPSON Born: 4/15/43 Died: 1/6/06 |

BUY THE BOOK: The Forgotten Hero of My Lai: The Hugh Thompson Story Amazon Books or Acadian House Publishing |

|

By Nell Boyce Skimming over the Vietnamese village of My Lai in a helicopter with a bubble-shaped windshield, 24-year-old Hugh Thompson had a superb view of the ground below. But what the Army pilot saw didn't make any sense: piles of Vietnamese bodies and dead water buffalo. He and his two younger crew mates, Lawrence Colburn and Glenn Andreotta, were flying low over the hamlet on March 16, 1968, trying to draw fire so that two gunships flying above could locate and destroy the enemy. On this morning, no one was shooting at them. And yet they saw bodies everywhere, and the wounded civilians they had earlier marked for medical aid were now all dead. As the helicopter hovered a few feet over a paddy field, the team watched a group of Americans approach a wounded young woman lying on the ground. A captain nudged her with his foot, then shot her. The men in the helicopter recoiled in horror, shouting, "You son of a bitch!" Thompson couldn't believe it. His suspicions and fear began to grow as they flew over the eastern side of the village and saw dozens of bodies piled in an irrigation ditch. Soldiers were standing nearby, taking a cigarette break. Thompson racked his brains for an explanation. Maybe the civilians had fled to the ditch for cover? Maybe they'd been accidentally killed and the soldiers had made a mass grave? The Army warrant officer just couldn't wrap his mind around the truth of My Lai. Before My Lai, Americans always saw their boys in uniform as heroes. Their troops had brought war criminals, the Nazis, to justice. So when the massacre of some 500 unarmed Vietnamese civilians by U.S. soldiers became public a year and a half later, it shook the country to its core. Many Americans found it so unbelievable they perversely hailed Lt. William Calley, the officer who ordered his men to shoot civilians, as an unjustly accused hero. But My Lai did produce true heroes, says William Eckhardt, who served as chief prosecutor for the My Lai courts-martial. "When you have evil, sometimes, in the midst of it, you will have incredible, selfless good. And that's Hugh Thompson." On that historic morning, Thompson set his helicopter down near the irrigation ditch full of bodies. He asked a sergeant if the soldiers could help the civilians, some of whom were still moving. The sergeant suggested putting them out of their misery. Stunned, Thompson turned to Lieutenant Calley, who told him to mind his own business. Thompson reluctantly got back in his helicopter and began to lift off. Just then Andreotta yelled, "My God, they're firing into the ditch!" Thompson finally faced the truth. He and his crew flew around for a few minutes, outraged, wondering what to do. Then they saw several elderly adults and children running for a shelter, chased by Americans. "We thought they had about 30 seconds before they'd die," recalls Colburn. Thompson landed his chopper between the troops and the shelter, then jumped out and confronted the lieutenant in charge of the chase. He asked for assistance in escorting the civilians out of the bunker; the lieutenant said he'd get them out with a hand grenade. Furious, Thompson announced he was taking the civilians out. He went back to Colburn and Andreotta and told them if the Americans fired, to shoot them. "Glenn and I were staring at each other, dumbfounded," says Colburn. He says he never pointed his gun at an American soldier, but he might have fired if they had first. The ground soldiers waited and watched. Thompson coaxed the Vietnamese out of the shelter with hand gestures. They followed, wary. Thompson looked at his three-man helicopter and realized he had nowhere to put them. "There was no thinking about it," he says now. "It was just something that had to be done, and it had to be done fast." He got on the radio and begged the gunships to land and fly the four adults and five children to safety, which they did within minutes. Before returning to base, the helicopter crew saw something moving in the irrigation ditch–a child, about 4 years old. Andreotta waded through bloody cadavers to pull him out. Thompson, who had a son, was overcome by emotion. He immediately flew the child to a nearby hospital. Thompson wasted no time telling his superiors what had happened. "They said I was screaming quite loud. I was mad. I threatened never to fly again," Thompson remembers. "I didn't want to be a part of that. It wasn't war." An investigation followed, but it was cursory at best. A month later, Andreotta died in combat. Thompson was shot down and returned home to teach helicopter piloting. Colburn served his tour of duty and left the military. The two figured those involved in the killing had been court-martialed. In fact, nothing had happened. But rumors of the massacre persisted. One soldier who heard of the atrocities, Ron Ridenhour, vowed to make them public. In the spring of 1969, he sent letters to government officials, which led to a real investigation and sickening revelations: murdered babies and old men, raped and mutilated women, in a village where U.S. soldiers mistakenly expected to find lots of Viet Cong. Not all soldiers at My Lai participated in the carnage. Some men risked courtmartial or even death by defying Calley's direct orders to shoot civilians. Eckhardt doesn't think these men were heroes, because they didn't try to stop the murderers. But Colburn thinks they did the best they could. "We could just fly away at the end of the day," he notes. The ground troops had to live together for months. The Pentagon's investigation eventually suggested that nearly 80 soldiers had participated in the killing and coverup, although only Calley (who now works at a jewelry store in Columbus, Ga.) was convicted. The eyewitness testimony of Thompson and Colburn proved crucial. But instead of thanking them, America vilified them. Many saw Calley as a scapegoat for regrettable but inevitable civilian casualties. "Rallies for Calley" were held all over the country. Jimmy Carter, then governor of Georgia, urged citizens to leave car headlights on to show support for Calley. Thompson, who got nasty letters and death threats, remembers thinking: "Has everyone gone mad?" He feared a court-martial for his command to fire, if necessary, on U.S. soldiers. Gradually the furor died down. Colburn and Thompson lived in relative anonymity until a 1989 television documentary on My Lai reclaimed them as forgotten heroes. David Egan, a Clemson University professor who had served in a French village where Nazis killed scores of innocents in World War II, was amazed by the story. He campaigned to have Thompson and his team awarded the coveted Soldier's Medal. It wasn't until March 6, 1998, after internal debate among Pentagon officials (who feared an award would reopen old wounds) and outside pressure from reporters, that Thompson and Colburn finally received medals in a ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. But both say a far more gratifying reward was a trip back to My Lai this March to dedicate a school and a "peace park." It was then they finally met a young man named Do Hoa, who they believe was the boy they rescued from that death-filled ditch. "Being reunited with the boy was just...I can't even describe it," says Colburn. And Thompson, also overwhelmed, doesn't even try. |

|

Hugh Thompson, retired with service in both

the Army and the Navy, recently addressed the United States Naval Academy

on the ethics of duty in combat. Mr. Thompson spoke at the annual fall

ethics lecture hosted by the Center for the Study of Professional Military

Ethics. In addition to addressing the Naval Academy, he set aside an afternoon

to sign copies of his new book, The Forgotten Hero, in the Midshipmen

Store, met with instructors on the core ethics course, and had an informal

dinner with a small group of midshipmen.

He began his presentation with a video clip

of his story taken from "60 Minutes" interviewing him about his experience

as a helicopter pilot in Vietnam followed by a subsequent trip back to

the village of My Lai. Then he filled in the gaps and took questions. His

story of courage and duty is taught in the required ethics course for midshipmen,

but Mr. Thompson was able to bring urgency to his personal account of My

Lai. This helicopter pilot was responsible for bringing a stop to the massacre

being conducted in and around the village of My Lai. His job was to protect

troops right outside of the villages and then draw enemy fire to his helicopter

while covering the U.S. ground troops. Often this required him to fly as

low as ten feet off the ground. Intelligence reports told American forces

that the enemy lay in wait in the village of My Lai.

At one point, Thompson had to return to the

base camp to refuel. He was gone less than an hour. When he returned to

the village, he and his two crew members noticed villagers strewn about

the ground. They also saw a mass grave site filled with bodies. Taking

a closer look, he immediately noticed the bodies were those of women, children,

and old men. Flying over the gravesite, he realized that some of

the people were still alive. Aghast at what he saw, and then spotting

a young child still alive, he asked one of the ground troops to escort

the child to safety. In response, the child was shot dead on the spot.

Coming to full realization, Mr. Thompson felt

Spotting three Vietnamese peering out of a

bunker, he vowed to not repeat the same mistake. Instead, he positioned

his helicopter between the Vietnamese and U.S. soldiers. "I was determined

not to let the men I was supposed to be protecting commit anymore such

acts," stated Mr. Thompson, remembering the incident. A short standoff

ensued before he was able to coax the noncombatant civilians, who turned

out to be ten people, not just three, out of the bunker, and he was able

to arrange for their removal to safety along with a small boy pulled from

the mass grave.

When asked if he would have fired upon his

own men, he responded, "I had already given my crew members the order to

fire back if fIred upon by the u.s. soldiers." The mission was subsequently

shortened from four days to hours after he reported the incident to his

chain of command.

When asked what he thought caused the ground

troops' actions that day and why his reactions were different, he adamantly

answered, "The quality of leadership found in their officers was poor.

We all had the same briefs on the operation, but their officers did not

follow their duty in leading their men." Still emotional about the

incident, he added that, "This is not war, and no American soldier should

consider it such." When asked why he personally made his choice, he carefully

explained, "I was raised in a strict family, probably considered abusive

by today's standards, but we were taught right from wrong, and that was

wrong." He spoke of the duty he was bound to honor by saving the lives

of noncombatants from needless killing and the action he needed to take

against his own comrades to change the situation.

He hopes that by speaking with people today,

specifically future officers, that he can instill a sense of responsibility.

His main message is, "Do the right thing, make the right decision, get

Mr.Thompson's presentation was part of the

fall ethics lecture series supported through the generosity of William

C. Stutt. The Center for the Study of Professional Military Ethics sponsors

this and a spring lecture series. |

|

| From the Los Angeles Times VIETNAM: CIVILIAN KILLINGS WENT UNPUNISHED Declassified papers show U.S. atrocities went far beyond My Lai. By Nick Turse and Deborah Nelson Special to The Times August 6, 2006

The men of B Company were in a dangerous state of mind. They had lost five men in a firefight the day before. The morning of Feb. 8,

1968, brought unwelcome orders to resume their sweep of the countryside, a green patchwork of rice paddies along Vietnam's central

coast.

Sept. 29, 1969 |

|

Agent Orange Victims Gather in Vietnam To Ask For Long-Overdue Help By Staff and Wire Reports Mar 28, 2006 Vietnam War veterans from the United States, South Korea, Australia and Vietnam gathered in Hanoi Tuesday to call for more help for the many victims of the Agent Orange defoliant used by the U.S. military. Deformed children born to parents Vietnam believes were affected by the estimated 20 million gallons of herbicides, including Agent Orange, poured on the country were brought to the conference as dramatic evidence of its effects. "The use of Agent Orange in Vietnam produced unacceptable threats to life, violated international law and created a toxic wasteland that continued to kill and injure civilian populations long after the war was over," said Joan Duffy from Pennsylvania. Duffy who served in a U.S. military hospital in Vietnam in 1969-1970, said the Agent Orange used there was more toxic than usual. "In an effort to work faster and increase production of Agent Orange, the chemical companies paid little attention to quality control issues," she said. "The Agent Orange destined for Vietnam became much more highly contaminated with dioxin as the result of sloppy, hasty manufacturing," she told the conference in Hanoi. Last March, a federal court dismissed a suit on behalf of millions of Vietnamese who charged the United States committed war crimes by its use of Agent Orange, which contains dioxin, to deny communist troops ground cover. The Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA) has filed an appeal, saying assistance was needed urgently as many were dying. The U.S. appeals court was expected to make a decision in April. Dioxin can cause cancer, deformities and organ dysfunction. Manufacturers named in the suit included Dow Chemical Co. and Monsanto Co.. VAVA chairman Dang Vu Hiep said Vietnam's lawsuit against U.S. chemical manufacturers was meant not only to help Vietnamese victims, but also victims in other countries. In January, a South Korean appeals court ordered Dow Chemical Co and Monsanto Co. to pay $65 million in damages to 20,000 of the country's Vietnam War veterans for exposure to defoliants such as Agent Orange. Due to problems arising from jurisdiction and the amount of time that has elapsed since the war, legal experts said it will be cumbersome or perhaps impossible for the South Korean veterans to collect damages. The chemical remains in the water and soil, scientists say. "Thirty years after the fire ceased, many Vietnamese are still dying due to the effect of toxic chemicals sprayed by the U.S. forces in Vietnam and many Vietnamese will still be killed by the chemicals," said Bui Tho Tan, a war reporter who suffers from throat cancer. "Those who committed the crime must be punished," he said. |

| The Beginnings of the Vietnam War Robert Streyar On September 2, 1945, representatives from the Emperor of Japan signed surrender papers ending World War II. On that same day a declaration of independence was signed by Ho Chi Minh and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was born. The proclamations said, "All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among those are, Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness." Now, if this sounds a lot like our own Declaration of Independence, that's because it is. Minh studied history while attending school in the United States. In 1919, Minh tried to convince President Wilson to endorse Vietnamese independence, but Wilson refused to meet with him. During World War II, Minh was an ally of the United States and the Americans had given him money and weapons so he could fight the Japanese. Minh was certain that this would be rewarded by the United States, and in return, they would support Vietnamese independence after the war. We didn't. Instead we supported a return of the French. At first, Ho Chi Minh tried to negotiate with the French. However, after talks collapsed, a war of independence broke out in Vietnam. From 1946 to 1954, we poured millions of dollars into coffers for the French military, so in effect we armed both sides. In 1954, the unthinkable happened. The French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu. Many people in the Eisenhower administration wanted to go to war and replace the French but President Eisenhower, who had just negotiated a perilous peace in Korea, was in no mood to send American boys to Vietnam.

But others in the administration had different ideas, including Secretary of State

Charles Foster Dulles. "I do

not believe that in this contingency, the United States would simply say

'too bad we're licked and that is the end of it.' We can raise hell and

the Communists will find it just as expensive to resist as we are now

finding it." Diem had spent most of his time out of the country and had no knowledge

of the inner workings of Vietnam. Because of this, he made two other

tragic mistakes, which seemed logical at the time, but would prove to be a

devastating for the Vietnamese. First, he ordered the French to leave,

which removed any kind of government in South Vietnam. Next, because he

suspected they were communists, Diem ordered the Chinese out of the

country. This destroyed the commerce of South Vietnam because the Chinese

were the middle men in Vietnam's economy. Now, when rice farmers brought

their crops to market to exchange them for necessary goods, no one was

there to trade with them.

Meanwhile, the English, neutrals in this conflict,

shipped supplies and arms to North Vietnam. We deferred mining North

Vietnam harbors because English ships were "welded" to the docks, and the

US did not want a diplomatic incident with England. U.S troops, and Viet

Cong considered certain corporate plantations off limits to combat. Rubber

plantations, fruit plantations were not involved in the conflict. If this

sounds like the banana wars of Central America (Hail, United

Fruit), it is strikingly similiar.

Vietnam is considered the ricebowl of Asia. So, the famous Domino theory

was advanced to justify propping up a puppet government in South Vietnam,

to deny verdant rice fields to the 'communists'. |